Summerville claims to be the birthplace of sweet tea, and Wadmalaw Island boasts producing the only tea grown in America. But both of those accolades might well have become Mount Pleasant’s claim to fame.

While looking through a copy of “Charleston Recipes,” the precursor of the locally revered cookbook, “Charleston Receipts,” area resident and novelist Josephine Humphreys noticed a recipe for cassina tea, a beverage the multi-generational Charlestonian admits she knew very little about. The recipe describes it as “one of the most delicious native drinks and compares favorably with most imported teas, if brewed properly.” Her discovery prompted her to dig further.

Humphreys found that in the early 20th century, the federal government aided the efforts of a Mount Pleasant farmer to produce the commodity for widespread retail distribution. In a report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, “about 7,000 pounds of cassina of three different kinds, namely green cassina, black cassina and cassina mate, were produced by different methods of manufacture. About thirty gallons of hot cassina beverage were served each day for fourteen days during the Charleston, South Carolina County Fair in 1922. The demand indicated very promising commercial possibilities for this beverage. Most of the 7,000 pounds of cassina manufactured during the course of the experiment were placed on the market in half-pound containers to further test the commercial possibilities of the product.”

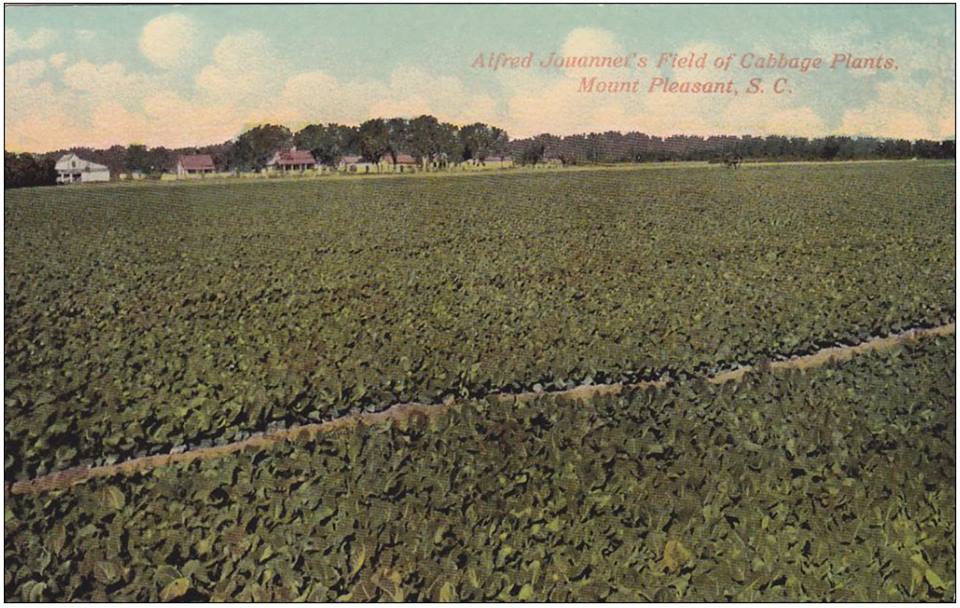

Dr. David Shields, distinguished professor at the University of South Carolina and author of a number of books and articles on the history of Southern food, has written on the topic of cassina tea. He writes that Alfred Jouannet arrived in Mount Pleasant in 1882 and purchased a large farm on Rifle Range Road. While growing asparagus, onions, cabbages and rye, Jouannet heard that locals once made a drink from the dried leaves of the cassina tree – also known as Christmas berry or dahoon holly – a species indigenous to the coastal areas of southeastern North America. After brewing a bit of it for himself, he discovered that it provided essentially the same boost found in tea and coffee. According to Shields, the cassina leaves actually contain theobromine, the stimulant found in chocolate, rather than caffeine. But regardless of the source of the kick, Jouannet’s product was expected by some to take the country by storm. An agricultural reporter wrote in the Augusta Chronicle in 1922, “I do not believe that I have ever gone on a more important mission than this one to Mount Pleasant.” A writer for the San Diego Union announced several years later that “Japanese producers and exporters of green and black tea which will come in competition with green cassina and black cassina are worried over this prospective new American industry.”

Humphreys remembered that her mother alluded to the consumption of cassina tea by local Native Americans. That anecdote bears a striking resemblance to the tale of Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon’s being offered a cup of “black drink” by an Indian girl when he came ashore in Florida, according to Shields. But for it to end up in “Charleston Receipts,” the benchmark of all things traditional in the Charleston culinary sphere, it must have also had an even more popular appeal, at least locally.

The cookbook’s instructions for brewing the tea require using only the leaves, as the berries are poisonous. The leaves are to be toasted in a hot oven and turned constantly until they are brown and crisp. They should then be crumbled by hand and stored in containers until they are ready for use.

Shields reported that by the end of 1922, “Jouannet’s production plant had three tons of the cassina tea ready for sale. He had cut the new growth leaves and cured them so they looked like tea. He could process 200 pounds a day at the cost of 5 cents a pound at his production site. It was anticipated that a secondary product would likely become popular as well – a syrup made from the leaves that could be added to soft drinks and ice cream.

But, alas, the consumption of cassina tea and any hope of its widespread use faded into the annals of history. The USDA concluded that, “apparently, the established customs of tea and coffee and the abundance and moderate prices of these commodities limited the demand and prevented the development of a market for a competitive product at that time.”

But thanks to Humphreys and Shields – and the age-old cookbook – it hasn’t been forgotten.

By Mary Coy.

Leave a Reply