Once upon a time it was Hunter Island. Then its name changed to Long Island. In the early 1900s, it earned the nickname “the Coney Island of the South.” Today, you know this 5.4-square-mile barrier island as Isle of Palms.

Home to just over 4,000 souls, according to the most recent census, Isle of Palms boasts a popular beach, numerous restaurants and shops, an elegant resort with two golf courses and is a premier summer destination for locals and vacationers alike. But why “the Coney Island of the South?”

This story begins in 1897, when Nicholas Sottile – progenitor of the well-known and highly regarded Lowcountry Sottile family – built the first home on the island as a summer getaway. He and his family had to hire a rowboat to get them there.

One year later, an entrepreneurially minded gentleman named Dr. Joseph S. Lawrence dubbed it Isle of Palms, in part due to its proliferation of sabal palms but primarily because he felt the name would be likely to attract tourists. Dr. Lawrence also promoted and later served as president of a company that built more than seven miles of track and trestle for horse-drawn then electric trolley cars to carry visitors from a boat landing in Mount Pleasant all the way to his island paradise.

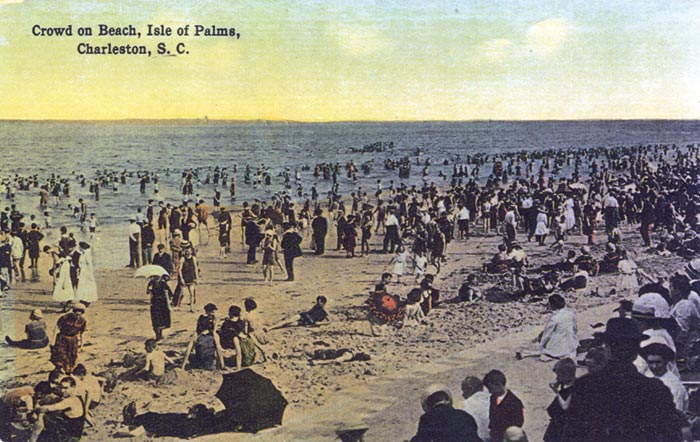

And that is where but the first comparison to New York’s Coney Island was born. That Brooklyn beach community had established regular service by horse-drawn trolleys in the early 19th century and by 1875 was transporting more than 2 million people a year. The huge influx of visitors to Coney Island spawned hotels, restaurants and an amusement park featuring such attractions as a carousel and the first roller coaster, the Switchback Railway.

The success of Coney Island and that venue’s similarity to Isle of Palms were clearly not lost on Dr. Lawrence. IOP quickly gained a luxury hotel and restaurant, and amusements began to appear  along the beachfront. According to newspaper reports of the era, early “horseless carriage” races were common on the miles of pristine sand and were so successful that the island’s sobriquet could just as easily have become “the Daytona of South Carolina.”

along the beachfront. According to newspaper reports of the era, early “horseless carriage” races were common on the miles of pristine sand and were so successful that the island’s sobriquet could just as easily have become “the Daytona of South Carolina.”

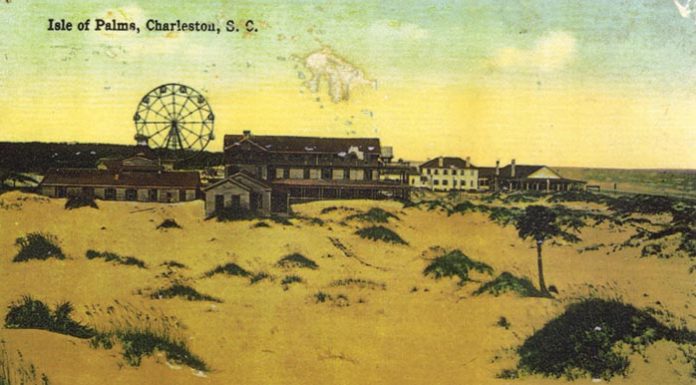

Those organized races soon faded in popularity as more and more sun and surf lovers sought out the island for day trips and longer excursions aboard the convenient trolley service. In 1912, another Sottile, James, further enhanced Isle of Palms’ growing reputation as the Coney Island of the South by creating an amusement park featuring a spacious pavilion with private dining rooms, a huge dance floor and a rooftop, open air observation deck.

Sottile added a steeplechase ride, a merry-go-round and a gigantic Ferris wheel said to have been visible from downtown Charleston on a clear day. That very Ferris wheel had begun its life at the  Chicago World’s Fair in 1892 and had found another home – where else? – at Coney Island before being moved to Isle of Palms.

Chicago World’s Fair in 1892 and had found another home – where else? – at Coney Island before being moved to Isle of Palms.

Visitors from as far away as Atlanta flocked to this new resort, picnicking, dining, dancing, riding the growing number of attractions and donning their modest if often uncomfortable “bathing costumes” for a dip in the temperate waters of the Atlantic.

As a resort and amusement area, IOP thrived until the post World War I years, then began to lose some of its luster, despite new roads and bridges that made the island much more accessible. A series of disastrous fires to the largely wooden structures in the amusement area in the 1930s further crippled the resort.

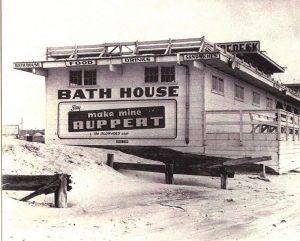

As a destination, Isle of Palms took an upturn in 1945 when local attorney J.C. Long bought 1,300 acres and set out to establish a complete residential community for vacationers and full-time residents alike. That same year, automobiles could travel all the way from Charleston to Isle of Palms using the Grace Memorial Bridge over the Cooper River and the newly-opened Ben Sawyer Bridge across the Intracoastal Waterway to Sullivan’s Island, and then onto Isle of Palms. New pavilions including The Lighthouse flourished, offering dancing, bathhouses, beer and refreshments.

A mini-resurgence of popularity for the remaining amusement area occurred, only to be dashed in 1954 when another spectacular fire consumed the iconic Hudson’s Pavilion, once host to the most famous dance bands in America and home to a shopping center, a bowling alley, the island’s first post office and much more.

The fire was a huge blow to Isle of Palms, which one year earlier had built a 1,000-foot fishing pier, banned auto racing forever on the beach and incorporated as a city. After that conflagration, Isle of Palms re-set its focus on becoming the desirable residential and vacation community it remains today.

One lifelong Isle of Palms resident who has vivid memories of that final phase of IOP’s “entertainment boardwalk” era is State Rep. Mike Sottile, R-112, who has also served as mayor of the Isle of Palms and is a grandson of Nicholas Sottile. His uncle, Salvatore Sottile, another former mayor of IOP, was serving as volunteer fire chief when the 1954 fire gutted the grand pavilion.

Mike Sottile himself was also on scene for that fire.

“I still have visions of it in my head because it was such a huge fire, and I was such a small child,” he said, recalling that to help the volunteer Fire Department, his father and others “just grabbed anyone they could and sent them down to fight the fire.”

“The fire was so hot,” he remembered, “that it blistered the paint on the merrygo- round at the Playland Pavilion across the street.”

Mike Sottile’s fonder memories of the entertainment area include his father’s habit of carrying a big book of tickets in his pocket so that his children could always ride the attractions.

“He was a popular guy because he’d give tickets to all the other kids, too,” he said.

Sottile recalled enjoying pony rides, go-kart racing, boat rides and watching teams play “half rubber” in front of Hudson’s Pavilion. He longed to play the pavilion’s pinball machines, but, in those days, the machines were off limits to minors because they could pay off multiple wins in cash.

“You could get a good burger most any place on the island and the fishing pier, where I had my first real job. It used to open at 5 a.m. for serious fishermen. It cost 50 cents then to use the fishing pier and in the evenings a lot of people just liked to walk it and enjoy the salt air. That cost 25 cents.

“Back then, the roads were paved with oyster shells, and there were sand dunes where all the houses now are along the beach. There were only about 1,000 people living on IOP, and most of the homes were between Breach Inlet and the Methodist church. We had one grocery store and one hardware store and two gas stations at the Inlet. I knew everybody on the island. Now it’s different.”

Asked if he felt that Isle of Palms could ever try to rekindle its early flame as “the Coney Island of the South,” Sottile pondered before answering: “It could be possible but difficult. The problem is there’s no space left to do it. Everything is zoned residential, and you’d never get any of it re-zoned commercial.”

So, for now at least, it seems that along with the Cyclone roller coaster and the Fourth of July hot dog eating competition, the title “Coney Island” will depart from the South and finally belong solely to that Yankee fun park up there in Brooklyn. Which, map mavens will note, is located at the southwestern tip of … Long Island.

By Bill Farley

Photos courtesy of Mike Sottile

Leave a Reply