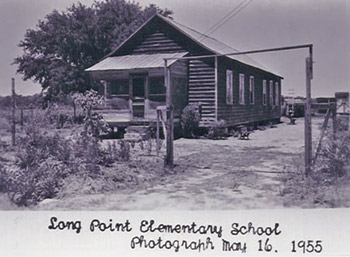

On a particularly scorching day in August, with the heat index stretching to 105, President of the Snowden Community Civic Association Freddie Jenkins and I ride to a significant Mount Pleasant structure now hidden but not forgotten. Diners at the nearby Waffle House on Long Point Road wouldn’t necessarily know that just a stone’s throw away, on a grassy four-acre lot, stands the last remaining African- American schoolhouse East of the Cooper. Now overgrown with weeds and vines that wrap around boarded windows and peeling paint, this structure once was a thriving center of learning. It served the Snowden community prior to the monumental Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled racial segregation unconstitutional.

“It’s very important to teach the younger generation about our culture,” said Jenkins. “They need to know where they come from to know where they are going.”

With the help of ongoing funding, this historic landmark that impacted and shaped many will be carefully transported up the road to where the Snowden Community Center sits and eventually reopened as a cultural arts center sure to give a glimpse into the region’s past. Future generations will see just what that schoolhouse looked like, but, most importantly, they will get a sense of the community, tenacity and encouragement fostered within those walls all those years ago.

“When I was 5 years old, I used to ride my two-wheel bike right to this one-room schoolhouse,” said Thomasena Stokes-Marshall, who also recalled walking with her parents on weekday mornings. “I look back on that time and reflect on what the community was like. We knew each other. We fed each other. There were no locked doors. There was a greater demonstration of care for mankind in general.”

“When I was 5 years old, I used to ride my two-wheel bike right to this one-room schoolhouse,” said Thomasena Stokes-Marshall, who also recalled walking with her parents on weekday mornings. “I look back on that time and reflect on what the community was like. We knew each other. We fed each other. There were no locked doors. There was a greater demonstration of care for mankind in general.”

Built in the early 1900s, this modest property is so much more than a place where cursive was practiced and equations were solved. It was here where unrelenting hope thrived and ambition was nurtured. Many pupils who passed through those doors went on to foster great positive change. Some even met their spouses there.

Long Point Schoolhouse alumna Stokes-Marshall was the very first African-American Mount Pleasant Town Council member, and the longest-serving member in the Council’s history. For 17 years, she dedicated herself to providing affordable housing in Mount Pleasant and stepped in when development threatened the livelihood of sweetgrass basket makers along Highway 17. Prior to her political career, she worked as a detective in New York City.

At age 75, Stokes-Marshall has spearheaded an oral history program in partnership with Citadel professors in which local elders recount just what life was like in the days when Mount Pleasant flourished with livestock, wild vegetation and medicinal herbs. Before the influx of countless neighborhoods and brick-and-mortar stores, fields of ripe watermelons, pecan, peach and fig trees and blueberry bushes once thrived. It’s Marshall’s hope that through this storytelling initiative, more people will take an interest in the African-American narrative and discover its contributions and milestones.

At age 75, Stokes-Marshall has spearheaded an oral history program in partnership with Citadel professors in which local elders recount just what life was like in the days when Mount Pleasant flourished with livestock, wild vegetation and medicinal herbs. Before the influx of countless neighborhoods and brick-and-mortar stores, fields of ripe watermelons, pecan, peach and fig trees and blueberry bushes once thrived. It’s Marshall’s hope that through this storytelling initiative, more people will take an interest in the African-American narrative and discover its contributions and milestones.

“If we don’t put a conscious effort to protect and preserve these structures, and they are torn down, we are wiping out history,” said Stokes-Marshall. “We can’t leave out history. It connects us to our past.”

Initially, when talk to save this schoolhouse surfaced, advocates discovered that current laws concerning historic preservation did not in fact protect this Mount Pleasant structure from being demolished. A study done by Dr. Richard Grant Gilmore, director of the College of Charleston’s Historic Preservation and Community Planning Program, shed light on the technology used to build it, which dates back to the 18th century. Gilmore, along with a team of graduate and undergraduate students, worked diligently to uncover the origins of construction of the now tree-shrouded structure.

African-American Settlement Community Historic Commission board members Freddie Jenkins, Pat Sullivan and Stokes- Marshall have been organizing efforts to raise funds since the news broke that the land where the school was located would be sold to a developer. While a fundraising event, which included a walkathon and baseball tournament, garnered a big turnout, monetary support is still needed to ensure this schoolhouse is successfully moved and restored to its original condition. The goal is for the interior to capture the essence of when school was in session. Photographs and artifacts from community members may also be interwoven into the center’s aesthetic.

“The Cultural Center will become a unique part of our tourism market East of the Cooper, and the Snowden community is at the pulse of something amazing,” said Historic Commission President John Wright, who has also helped with efforts to bring the project to fruition. “The center will be a benefit for generations to come.”

While the actual move is slated for sometime in September, just when the new center will open depends on the financial support the project receives.

The schoolhouse was transformed into a residence after it closed in 1953, following the opening of nearby Jennie Moore Elementary. In 2000, the well-made structure managed to survive an interior fire and has withstood a slew of hurricanes throughout the years. Beneath new additions and upgrades, this landmark still remains intact – a testament to the spirit of the people who built it with their own hands and to the teachers who worked hard to provide students with curriculum that would engage and excite.

Despite the years of wear and tear, there’s a resilient beauty in this building, whose roof is heavy with fallen leaves and branches. It was built by those who wanted to see a brighter future for their youth at a time when segregation hindered access to education for all.

Snowden is one of the oldest Gullah-Geechee communities formed after The Civil War by freed slaves. Its close proximity to the Wando River allowed residents to shrimp, crab and fish both for profit and personal use. A self-sustaining enterprise that flourished in the days following slavery, residents set up their own farms and catapulted the region’s agricultural landscape to new heights.

“Land has always been the fabric that has woven us together,” said Stokes-Marshall. “Land offered us a community where we could survive.”

The news of the schoolhouse’s relocation prompted a final walk-through back in June, where former students, politicians, press and community members made their way up the sturdy steps for an afternoon of nostalgia. All look forward to the day when this landmark is restored and will serve the community in a new way.

“For me, preservation is a passion that I don’t think will ever turn off,” said Sullivan. “It’s in my DNA. It comes from inside.”

“My mother went to school here,” said Jenkins. “I want to see this done. It will be so rewarding to know that part of my history, my legacy, will live on.”

Want to be a part of history and see this historic landmark, which predates The Civil Rights Movement, take shape as a cultural center? Log on to www.gofundme.com/long-point-school to make a donation, and visit www.scca-sc.org for more information.

By Kalene McCort

Leave a Reply