Although I didn’t realize it at the time, my longtime relationship with hurricanes started in 1969 when Camille hit the Mississippi Gulf Coast. A Category 5 storm with 190 mph sustained winds, Camille was the most powerful hurricane ever to make landfall in the United States. All the destruction and death caused by this act of Mother Nature happened one day after I left Biloxi, Mississippi, where I was training with the U.S. Air Force.

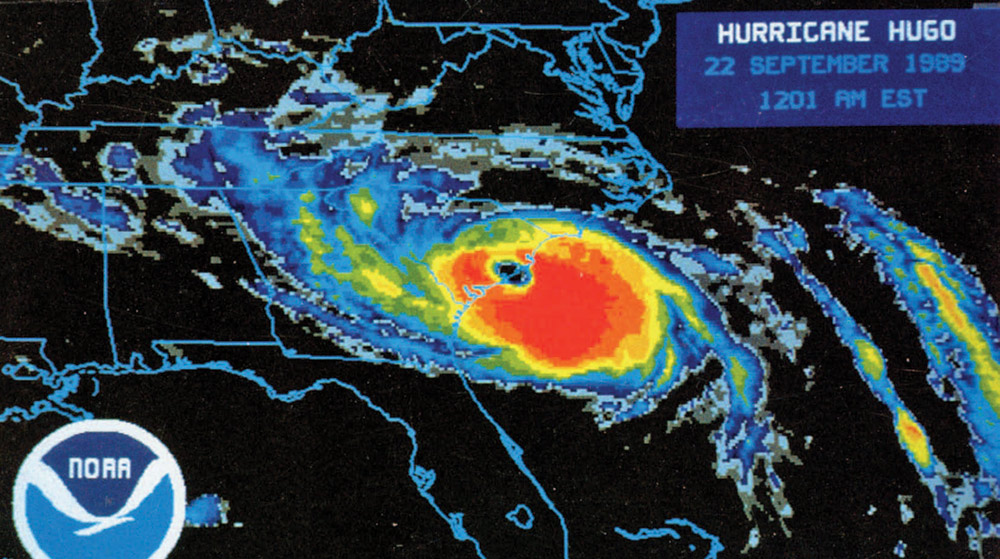

There was no Weather Channel, internet or sophisticated software to fully document Hurricane Camille back then, but advances were well underway by 1989 when Hurricane Hugo struck the coast of South Carolina. Founded in 1982, the Weather Channel took delight in visiting the historic city of Charleston and the surrounding islands. Viewers were able to instantly see the horrific results of this fierce hurricane that slammed into the coastline during high tide the night of Sept. 21.

Hurricane Hugo’s high winds and pressure were quickly approaching the South Carolina shoreline while my art director and I were feverishly working to make the impending deadline for East Cooper Magazine, the predecessor of Mount Pleasant Magazine. Everyone around me was frantically preparing for what ended up being a Category 4 hurricane when it hit South Carolina. My focus was getting the magazine completed and to our printer in Florida.

The trouble was that with Hugo on the way, the last flight out of Charleston International Airport was already gone. I received a call from my wife, Kim, who knows firsthand (for 30 years now) how passionate I am about my craft. She knew I would do anything to get my magazine to the printer, even facing the wrath of Hurricane Hugo. I can remember her purposeful words: “You know Bill, the only way to get East Cooper Magazine to the printer is to drive to Columbia and get it on a flight from there.”

Those were the exact words I needed to hear. I packed up the family and the material for East Cooper Magazine and headed to Columbia before the rest of the Lowcountry’s population evacuated and clogged up the highways leading out of Charleston. It was the right call. Early the following morning, I sent my magazine to the printer, driving to the Columbia airport to place the material on one of the last flights out of South Carolina’s capital city.

From there, we headed to Charlotte, as Hugo would do a few days later. I had no idea I would be facing the wrath of that violent storm, and that later my passion for publishing would lead me into the path of similar hurricanes.

After Hugo ran us out of Charlotte, we headed to Chimney Rock. Soon after, we decided to return to Mount Pleasant. The reports of power outages and the devastation caused by this massive hurricane caused anxiety for the whole family. As we edged closer to our home, the anxiety intensified, though I tried to keep it to a minimum. After all, we hadn’t seen for ourselves what had really happened in Mount Pleasant, Isle of Palms or Sullivan’s Island. As a family, I knew we needed to keep as calm as possible because we didn’t know what was ahead of us.

As we traveled closer to Charleston, Hugo’s destruction became more obvious with each mile. Like everyone around us, we were in a bit of a daze. Everyone’s world had been turned upside down overnight. Loud and clunky generators could be heard throughout East Cooper. For those of us lucky enough to have one, they were the only source of electricity. Fortunately, at the time, the office of East Cooper Magazine was on the same electrical grid as the old East Cooper Hospital, where Vibra Hospital of Charleston stands today. We had electricity, and my small, nondescript office became a hub of activity. It seemed like everyone in town passed through our doors at one time or another. We really didn’t know what to do. My family, as well as everyone else, was dealing with the essentials, but our little publishing office was attracting Hurricane Hugo storytellers. The two most common questions were, “Where were you when Hugo hit?” and “How bad did your home get hit?”

We had all lived through a horrific storm and could tell our stories in vivid detail and in heartfelt dialogue. After all, we were all survivors of this massive storm that had invaded our South Carolina shoreline, taken 61 lives and caused damages of $9.47 billion in 1989 dollars.

As time went on and the flow of photographers, writers, editors and friends continued through our doors, I had an epiphany. I couldn’t support anything through advertising because my clients were devastated. Everyone was dealing with surviving. Some were just packing up and heading out of town. Since it seemed everyone loved telling their stories – why couldn’t we tell the story of Hugo? Why couldn’t we publish a 100-page magazine titled Hurricane Hugo – Storm of the Century?

We spent weeks encouraging survivors to submit their stories and talking to newscasters, including Bill Walsh and Rob Fowler. We even interviewed Bob Sheets, head of the National Hurricane Center at the time. Sheets had gathered infrared satellite images of Hugo at different times, showing its massive strength as it smashed into our coast. Every member of the Storm of The Century staff was a survivor. Each day and night we would spend hours and hours preparing Hugo stories of survival, paired with numerous photos of destruction for our documentary.

As we sent my first-ever hurricane publication to the printer, the heaviness and anxiety Hugo had caused each of us was lifted off our shoulders. It was as if we had all gone through a Hurricane Hugo therapy session. It was an extraordinary feeling. It complemented the feeling I had knowing that this documentary we were publishing would be around long after I’d enjoyed my time on this planet.

Parts of Charleston, Mount Pleasant and the Islands that dot our Carolina shoreline were still a mess when our keepsake magazine hit the newsstand. Everyone wanted a copy. They treated it like their personal Hugo journal. The pictures of devastation and stories of survival were something they knew they would pass down to their children.

The process of documenting Hugo and telling the stories of survivors and the popularity of our historic document encouraged me to take up hurricane chasing.

And, over time, I became up-close and personal with other hurricanes, as well as their survivors: Hurricane Bob, which hit Cape Cod and New England in August 1991; Hurricane Andrew, which battered South Florida in August 1992; Hurricane Bertha, which blasted Wilmington, North Carolina, in July 1996; Hurricane Fran, which also hit Wilmington in August 1996; and Hurricane Georges, which struck South Florida and Key West in September 1998.

With Hurricane Andrew, which is a story for another time, I became close to Florida’s Division of Emergency Management. For several years, our little South Carolina company published the program for the Governor’s Hurricane Conference, the largest hurricane conference in the nation.

Documenting Hurricane Hugo and Hurricane Andrew were my most adventurous publishing undertakings and put every aspect of my craft to the test. I learned that even in the harshest of weather conditions and amid utmost destruction, communities still strive to pull together – and they still need to tell their stories. Even years after the storms, I continue to tell my readers about the hurricane stories and adventures in Mount Pleasant Magazine.

To hear about my adventures during Hurricane Andrew and the effect it had on South Florida, visit hurricanemagazines.com/Andrew.

By Bill Macchio

Can you still purchase the magazine about hurricane Hugo?

Yes, Janet you can. Check out http://hurricanemagazines.com/hurricanes/1989-hurricane-hugo/