Twelve-hour workdays with few or no bathroom breaks. Pay that’s nowhere near a living wage. Children under the age of 12 working long hours in dangerous jobs. We wince when we hear of these conditions in third-world countries. But workers in the United States faced these same injustices for many years.

Twelve-hour workdays with few or no bathroom breaks. Pay that’s nowhere near a living wage. Children under the age of 12 working long hours in dangerous jobs. We wince when we hear of these conditions in third-world countries. But workers in the United States faced these same injustices for many years.

In the Lowcountry, the hellish job of phosphate mining replaced the antebellum plantation system, offering slave-like work environments for both black and white laborers. Oyster factories employed children whose labor resulted in sore and bleeding hands as they shucked buckets of oysters for up to 12 hours a day. Many locals took jobs with meager pay at the cigar factory where they stood for hours on end at their work posts, immersed in the stagnant air and overpowering smell of tobacco. Female workers often experienced sexual harassment and even exploitation by their male supervisors, and black workers were paid far less than their white coworkers doing the same jobs.

As the years passed, workers across the country began to protest inhumane (and often dangerous) working conditions. On

Sept. 5, 1882, 10,000 workers in New York City marched from City Hall to Union Square to advocate for an eight-hour workday. This is considered by some to be the first observation of a “labor day” in the country. The increasingly vocal labor movement continued to bring public attention to the social and economic injustices inflicted upon many American workers, demanding laws to protect them — among them a 40-hour workweek, a minimum wage and the illegalization of child labor. By the 1890s, dozens of major cities were celebrating the sacrifice and contributions of the everyday worker with annual parades and festivities. On June 28, 1894, Congress officially designated the first Monday in September as a legal holiday for public recognition of the importance of the American worker.

But even with this official recognition and the passing of landmark legislation to protect workers, many Americans continued to struggle with dire working conditions and to experience abuse on the job well into the 20th century.

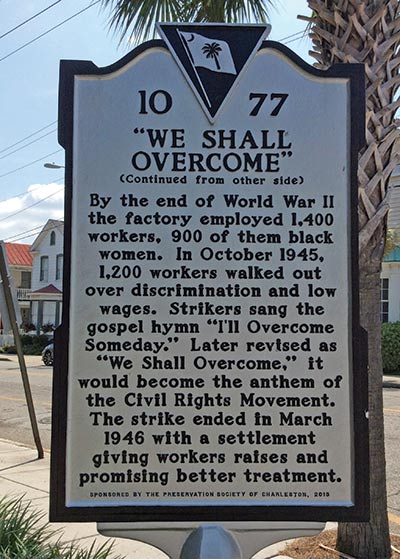

One of the most significant events in Charleston’s labor history occurred in October 1945, when hundreds of black and white employees of the American Tobacco Company on East Bay Street refused to work in an effort to establish better pay and racial and gender equality in the workplace. For five months, workers picketed and sang spirituals, adopting the hymn “We Shall Overcome” as their anthem. Twenty-four years later, African-American hospital workers at the Medical University of South Carolina protested substandard pay and demanded their right to lodge credible work-related complaints to the hospital administration without fear of losing their jobs. That three-month long strike underscored the rights of workers to be heard and is considered one of the most important local achievements in the labor movement as well as the civil rights era.

So, when we celebrate Labor Day as the official end of summer fun with picnics, cookouts and trips to the beach, let’s remember that what we are really celebrating is the progress that has been made (and continues to be made) in the quest for safety and fairness in the workplace and to salute the men and women of the American workforce, both now and in the past, for their contributions to the success and well-being of our country.

By Mary Coy

Leave a Reply