The batter slaps a bouncer into the hole on the left side, just out of the reach of the third baseman. The shortstop, who almost always possesses the strongest arm in the infield, glides easily to his right and snatches the ball on its third hop, sets his feet and fires a bullet across the diamond. His accurate throw thuds into the first baseman’s waiting mitt, arriving at the bag a half step before the fleet runner’s foot lands on the bag.

This scenario has played out in the most symmetrical of games for 175 years or so in hallowed venues such as Yankee Stadium, Ebbets Field and Fenway Park and on a multitude of minor league, high school and recreational league facilities from Freehold, New Jersey; to New Boston, Texas; to Emeryville, California.

Whoever determined the dimensions of a baseball diamond — and there has been great and raucous debate concerning who that genius actually was — was blessed with a prescience unmatched in the annals of sport. How could he have known, nearly two centuries ago, that a square with four 90-foot sides would always remain the perfect shape on which to play a game that would capture the imagination of a nation, serve as a testing ground for American race relations and, in East Cooper, produce fierce competition, pure joy and fond memories that remain nearly half a century after Sunday afternoon baseball disappeared from the dusty fields of East Cooper’s African American communities?

From somewhere around 1917 or 1918 — nobody seems to know for sure — until the 1970s, baseball was the most popular form of entertainment in black enclaves from Sullivan’s Island to Mount Pleasant to Cainhoy. Today, many former players who spent Sunday afternoons competing on fields that, for the most part, are long gone, look back fondly on those days and enjoy reminiscing about the competition, the relatively huge crowds and the game they still cherish.

“It’s in my blood,” said Joseph “Dune” Fordham, who is now 73 but still plays on a traveling baseball team and a traveling softball team. “If it rained, I was sick because I didn’t get to play some ball. My father said he hoped he didn’t die during baseball season because ‘you probably won’t come to my funeral.’”

Isaac Singleton, 69 years old and the youngest former player interviewed for this story, agreed that admiration for the game of baseball was among the most important reasons he looked forward to Sunday afternoons in East Cooper.

“I fell in love with the game, and I really enjoyed it when I started pitching,” he said.

“I fell in love with the game, and I really enjoyed it when I started pitching,” he said.

“I love baseball. I was the first one to throw a breaking ball,” Wesley Wigfall, 84, added. “The other team would be thinking, ‘We’re gonna lose. Look who’s in the bullpen.’ I would fool the batter and the catcher. I used to dream I was playing baseball. I’d be in church thinking about baseball.”

“I grew up listening to games on the radio, especially the World Series,” William Richardson, 74, said. “And I couldn’t wait for Sunday to get here.”

Just about every black community in Mount Pleasant and its environs had a baseball team, including Snowden, the Old Village, 4 Mile, Remleys Point, Buck Hall, Santee, Sullivan’s Island, Tibwin, 10 Mile, Cainhoy and probably more. They sported names such as the Mount Pleasant Trojans, the Laing School Braves, the Cainhoy Sweepers, the Sweet Shop Sluggers and the Mount Pleasant Bums. The youngest players were 15 or 16, and many team members continued competing well into their 40s and 50s. The season always started on the Monday after Easter. It was the only game not played on a Sunday.

“We learned from the older guys, and the competition was fierce,” said Aaron Green, 73.

The versatile Wigfall, who was comfortable at every position except catcher, was among the most talented players in the league, while others over the years have reached legendary status in East Cooper. They include pitcher Freddie “Iron Man” Bryant; catcher John L. Green; James German, who played with the immortal Willie Mays in the military; left-handed hurler Douglas Richardson; and John Jones, who pitched for the Sullivan’s Island team and could deliver the ball with either arm.

Joseph Jones, 78, was among the few East Cooper players who went on to college baseball at Denmark Tech from 1958 to 1960.

To East Cooper’s baseball players, however, no one ever attained the pinnacle reserved for Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play Major League Baseball in the modern era. Robinson’s influence was so strong that among the six players interviewed who have a favorite professional team today, four said they root for the Dodgers, a team that long ago left Brooklyn, where Robinson earned his Hall of Fame credentials.

“Most black kids really got into baseball when Jackie started playing,” said Jerome Parker, 77. “When Jackie came into the league, it gave you a drive. If he can do it, I can do it. It made you feel proud.”

“We didn’t have many heroes, but now we had a hero for the first time,” Fred Lincoln, 74, added. “He was an inspiration to so many people. Jackie really tweaked everyone’s interest in baseball.”

Major League Baseball was integrated on April 15, 1947, when Robinson broke in with the Dodgers, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that baseball become a black and white sport in East Cooper. A league that eventually grew to 24 teams was formed with integrated teams from Charleston and West Ashley, and, for a time at least, the crowds that came out to watch on Sunday afternoon were larger than ever in and around Mount Pleasant.

Sadly, the league — and organized baseball — didn’t last much longer in East Cooper, for one reason or another. Parker said the Vietnam War was to blame because most of the players left home to fight in Southeast Asia.

“When we came back, the kids were playing basketball,” he said.

Green pointed out that the National Basketball Association was better at promoting its stars than Major League Baseball, while Lincoln lamented the small crowds that show up for high school baseball, compared with the larger numbers at basketball and football games. Fordham’s opinion is that a financial crisis brought on by accusations of stolen money killed the league.

Regardless of what caused the demise of African American baseball in East Cooper, the roar of the crowds, the fierce competition and the love of the game live on among those who counted the days until Sunday afternoon arrived.

“It was America’s pastime, and it was definitely the pastime in black neighborhoods in the Lowcountry,” Green said.

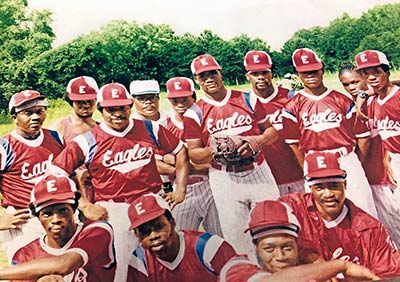

Black Baseball East of the Cooper Photos

By Brian Sherman

This was a great article that chronicled

The East Copper Baseball Leagues and it’s players. African Americans in the East Cooper were very family oriented, and everybody new each other. Do a story on how Blacks lost there homes, villages and communities after Hugo. Thanks for this article.