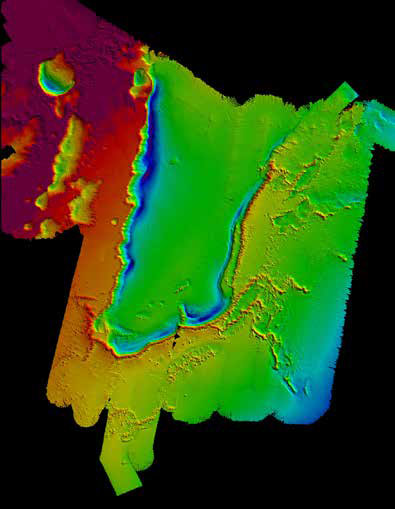

Try to imagine a towering hillside nearly five stories taller than the iconic steeple of St. Matthew’s Church in downtown Charleston. Next, think about that colossus 85 miles long – vast enough to stretch unbroken from Mount Pleasant to Conway.

Now let your mind’s eye transport that massive mound 160 miles off the South Carolina coast and submerge it to the ocean floor half a mile deep, where the pressure would crush a beer can with trash-compactor-like reliability, and it’s so pitch dark that a fish couldn’t see a fin in front of its face.

That’s exactly what “Deep Search 2018” scientists discovered – much to their amazement – when a team from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Bureau of Energy Management (BOEM), the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), seven academic institutions and a private company set out to explore sea floor mounds spotted through sonar mapping along South Carolina’s coast. The study’s purpose is to investigate three primary habitats: deepwater coral, canyons and methane seeps in the area. Researchers want to learn about animals that live there and understand the oceanographic, geologic and geochemical makeup of the waters.

Their investigation required several missions aboard the manned deep-sea research submersible Alvin, owned by the U.S. Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Research team leader Dr. Eric Cordes called one area they explored, the Richardson Ridge, “a huge feature,” adding, “It’s incredible that it stayed hidden off the U.S. East Coast for so long.”

Dr. Michael Rasser, a marine ecologist with BOEM, was among the scientists traveling aboard Alvin to another area on the excursion. He described it as “beautiful.”

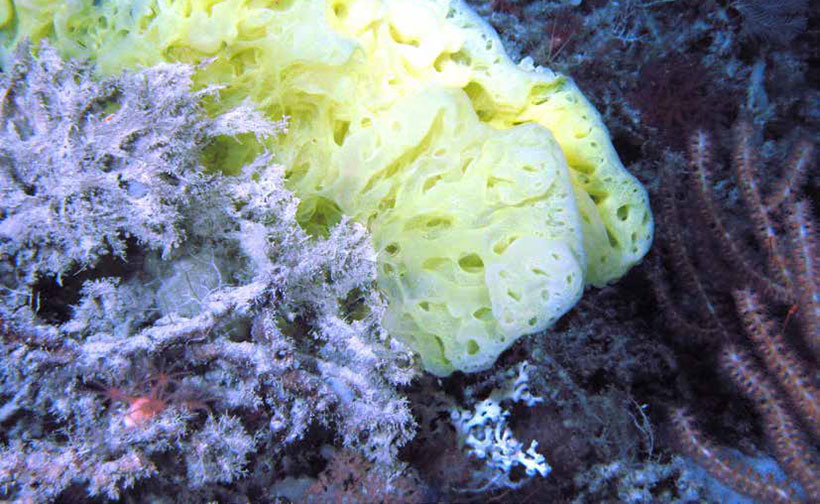

“The color palette is unique, really different from that of tropical coral. It was amazing to get ‘up close and personal’ to witness the colors of the lophelia coral and to see its little polyps alive and moving at such a tremendous depth,” he related. “Other types of corals provide color variety. … In some of the places we dove to, we were literally ‘going where man has never gone before,’ and all the scientists on the expedition were really excited about what we found.”

“Scientists live for these discoveries and what new things they can teach us about our world. It’s especially gratifying to see that people outside the scientific community are equally excited about what we found.”

Is the deepwater coral that was discovered different from its relatives found in shallower, warmer waters? Dr. Rasser noted that “Deepwater corals are similar to their relatives in shallow water. Both types extend tentacles from their skeletons to feed on marine debris and zooplankton. Both types eventually die and leave their skeletons behind, forming reefs and atolls and providing habitat for fish and other marine fauna.”

One major difference, he said, is that most reef-building corals contain photosynthetic algae, while lophelia coral do not. They have polyps with an opening surrounded by tentacles that sting their microscopic prey before ingestion, which is how they get their nutrition.

Over and above the pure scientific value of the astonishing find off South Carolina’s coast, if this discovery is connected to other areas of deepwater coral, it could improve their resilience.

Deep Search 2018’s astonishing discovery comes at a time when concerns exist over the fate of shallow water coral as a consequence of the warming of the seas and technological developments. For example, seismic air guns produce short pulses of sound – similar to sonograms – that bounce off the seabed to provide information about whether there is oil or natural gas beneath the ocean floor.

The scientists plan to take one more excursion in 2019 before finalizing their analysis and issuing a report in 2022. What does this mean to policymakers in Washington, D.C.? Dr. Rasser confirmed that “shallow water coral is being threatened by climate change and warming of the seas, and deepwater coral could be in danger as well. That’s something we all want to learn more about.”

Dr. Rasser said it is important to collect information so we can understand and learn how to protect sensitive habitats before permitting private companies to search for oil and gas deposits. He pointed out that it will take a few years to collect and analyze the necessary data.

“We have to learn more about how coral fits into the ecosystem, how the elements of the coral reef are connected and how the Gulf Stream functions as a sort of superhighway for coral larvae to move from place to place,” Dr. Rasser said. “Whether the issue is global warming or offshore drilling, scientists won’t make the ultimate decisions about how to protect sensitive environments such as the Richardson Ridge coral. The relevant government agencies will.”

“Their decisions won’t be made on a single study but on the body of evidence and experience available to them,” he added. “That’s one major reason why we conduct these expeditions – to collect data and provide accurate information to inform those decision-makers about these important marine habitats.”

By Bill Farley

Leave a Reply