We’ve all heard stories about wildly unfortunate individuals who have been struck by lightning. Then there are those rarest of rare people who have been struck twice.

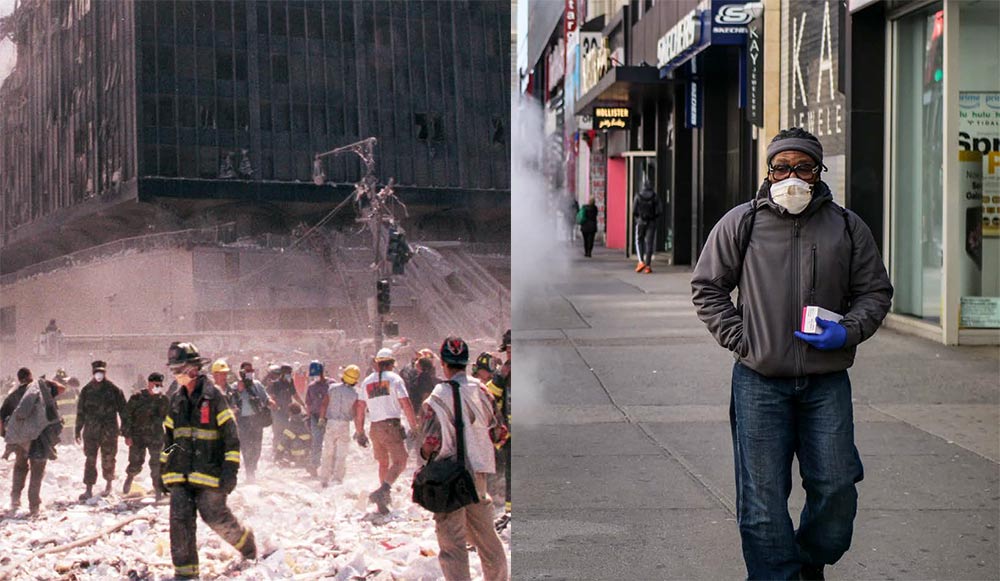

Meet Ed Bimonte, musician, entrepreneur and dedicated New Yorker. No, he wasn’t one of those individuals struck by lightning twice. But he did survive the aftermath of our nation’s most devastating terror attack and he is right now up to his masks and surgical gloves in trying to survive yet another calamity that has befallen his beloved city.

On a bright, sunny early fall morning in 2001, Bimonte gazed out the window of his apartment at 71 Broadway in lower Manhattan. Looking just past the famed Trinity Church he was shocked to see an airliner smash into a New York landmark.

The date was September 11, which we all now know as 9/11. Bimonte had just watched as a few blocks from where he stood the second passenger plane hijacked by the terrorists smashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center.

You might not have heard of Bimonte, but you may well have heard him. A drummer by trade, he has provided percussion for many great pop, rock and R&B artists including The Platters, The Drifters and Mick Taylor, and even spent a year on the road touring with Holiday on Ice.

He’s no stranger to the Lowcountry, having performed as a part of the Spoleto Festival in 1983 with rock and blues artist Diane Scanlon. He has also visited his brother Eddie and wife Kim—both accomplished professional musicians themselves—at their home in Mount Pleasant.

All this puts Bimonte in a unique position to compare and contrast life in New York right after the death and destruction at the World Trade Center and the medical crisis gripping the city and its people today.

He recalled how his world changed moments after he saw that airliner impact the World Trade Center tower.

“I got out of my apartment,” he said, “and headed south and away from the site. You couldn’t even walk in that direction. I couldn’t see my hand in front of my face. There was ash everywhere and I was stepping over burning human flesh in the streets.

“I had no idea that I wouldn’t be able to go home for almost three weeks—September 27 to be exact.”

While he was banned from returning to his apartment, Bimonte camped out with a former girlfriend in Greenwich Village. Between the pets he had grabbed up from home and his host’s pets, they shared her apartment with nine cats.

“I wouldn’t leave them behind, and they weren’t letting anyone go back into what was now known as Ground Zero,” he said.

Once it was possible to move about the city, Bimonte immediately noticed a big change.

“Life was compartmentalized,” he said. “The National Guard was camped out in front of my building. You needed ID to go south of Canal Street, even if you lived there. That was the clear line—below Canal and above Canal. Below was chaos. Above, the city was functioning normally. People were going about their business as usual.”

When he finally received clearance to return to his apartment, he said, “The taxi that took me there couldn’t go below Fulton Street on the FDR. I had to load my belongings on a hand truck and drag them about a mile to my home. Along the way, the only vehicles on the streets were military Jeeps and dump trucks filled with debris from the Twin Towers.”

Bimonte recalled registering with Safe Horizon and the American Red Cross, agencies dedicated to helping people after a disaster, and “they were on top of things immediately.”

Even FEMA, sometimes criticized for its post-disaster work, was “unbelievable.” He even received help with his moving expenses.

Fast forward to 2020. Now living in Gramercy Park on 19th Street between 1st and 2nd Avenues, Bimonte finds himself in the midst of a hospital district (his “neighbors” include Bellevue, Beth Israel, Hospital for Joint Diseases and NYU Hospital) in the epicenter “hot spot” for the deadly COVID-19 virus that has brought life throughout America to a standstill.

“Life in the city is different today,” Bimonte said. “For one thing, this time the entire city, and the world, is affected. It’s eerie, like a Twilight Zone episode that I’m living in every day. When I go out, I only see about 10 percent of the people I’d normally see. At night, that number drops to maybe two percent. Those people who do venture outdoors are all wearing face masks and social distancing.”

Bimonte got that message loud and clear. When he goes outside, he wears four surgical masks and an outer, breathable wrap over his face. “At night, I also carry Mace,” he added, “just to be on the safe side.”

As for the public assistance he has sought in the time of COVID-19 in New York, Bimonte said, “At first, you couldn’t even get through to the state government’s website. It kept crashing because millions of people were filing for unemployment. Fortunately, they were able to fix their problems so it’s possible to file for some much-needed help.”

On the other hand, Bimonte has an “up close and personal” perspective on the overloading of Manhattan’s medical facilities. Not long ago he passed by the city coroner’s office, where a green mesh fence had been erected to shield from view the refrigerated tractor trailers lined up to receive the bodies of the dead.

“There’s just no other place to put all the remains of the COVID-19 pandemic victims,” he shared.

“One of the things that troubles me every day is that the hospital workers on the front line of this pandemic often don’t have the PPE they need to do their jobs safely,” he added. “I’ve gone to Beth Israel Hospital and given them what I could from my apartment.”

While Bimonte has been “struck” by two very different kinds of “lighting” in Gotham, he has no plans to move.

“I’m a New Yorker,” he said proudly. “It’s who I am.”

By Bill Farley

Leave a Reply