Illuminated on October 1, 1876, the Morris Island Lighthouse stood sentinel as a literal beacon of light alerting ships that they were approaching Charleston Harbor. By the 1950s, erosion was threatening to destroy the landmark. Lighthouse keepers served here until 1938, when they could no longer safely inhabit the island.

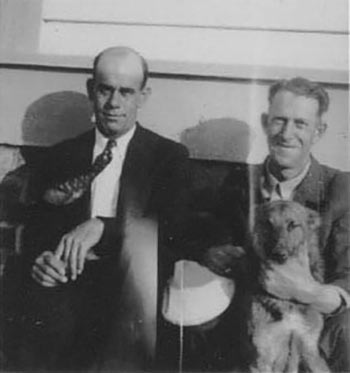

William Hecker, along with W.A. Davis, were the last two lighthouse keepers to reside on Morris Island. According to a list reconstructed by Lighthouse Service payroll records, family histories and other historic records, Hecker served as a Morris Island lighthouse keeper from 1925-1938. Davis’ service is listed more broadly as the 1920s and 1930s.

Hecker’s granddaughter, Violet O’Neill, shared recollections of the family’s time spent living on Morris Island thanks to information gathered through anecdotal accounts from her mother, Alice H. O’Neill, and her Aunt Esther, both deceased. Although these memories paint only a partial picture, what she and historical documents can substantiate provides a fascinating behind-the-scenes glimpse into the lives of the individuals who worked and lived at this cherished local landmark.

The iconic lighthouse is all that remains today, but at the advent of Hecker’s service on Morris Island, there was a residence for the lighthouse keepers and their families, as well as outbuildings accessed by an extended walkway, which was attached to a boat dock. Hecker’s wife, Esther, and the five children accompanied him during his Morris Island stint. It was common for many keepers to bring their families with them, and it is believed that Hecker may have requested the Morris Island gig because he wanted to be closer to his family. They would later have two more children after leaving the island.

According to stories from Alice O’Neill, Morris Island always had two keepers who would take turns tending the lighthouse. Hecker, a Merchant Marine who served in the Coast Guard, never discussed his lighthouse keeper duties and what they entailed, but the National Park Service relates that in addition to operating the light on a daily schedule, a few of a keeper’s primary responsibilities encompassed repairs, maintenance and emergency response.

Secluded like “The Swiss Family Robinson,” Hecker’s children had an entire island of their own to explore, but the lighthouse was considered off limits. “I know that discipline was really strict,” related Violet. Despite the lighthouse being forbidden, her mother Alice possessed fond memories of growing up on Morris Island and described it as a fun childhood. One aspect that may surprise readers about an island child is that Alice never learned to swim. Fortunately, it never became an issue.

While it sounds unfathomable today, when Hecker’s family first arrived, traversing the length of the island was tiring, so Hecker brought over his car—not an easy task in those days. He ingeniously devised a floating pontoon of three row boats tied together, then balanced his Model T on top and drifted it over to Morris Island. Hecker often drove the car to a section of the beach where the family would picnic and relax on his days off. Perhaps reflecting the resourcefulness of that era and the challenges of accessing supplies, when the car finally quit running, the Hecker and Davis families used it as a chicken coop.

All of the Hecker’s children were born in Charleston except for one, Esther, who was born on Morris Island. When Mrs. Hecker went into labor with Esther, inclement weather stirred rough seas, preventing safe passage to Charleston for the delivery. Braving the elements, Hecker picked up their family physician, Dr. Lebby, in his boat, but by the time they arrived back at Morris, Esther had already been born, earning her the nickname of “storm baby.”

For the children’s schooling, a teacher named Elma Bradham came by boat each Monday and stayed with the family all week before returning to her Johns Island home on Friday. According to Save the Light, Inc. — a nonprofit that bought the Morris Island Lighthouse in 1999 and later transferred ownership to the state — at that time, the Charleston County school system would provide a teacher to any barrier island with at least five elementary-aged children.

All of Hecker’s children are now deceased. Violet wishes the family could have recorded a more thorough account of the experience for posterity. “Time got away from us,” she lamented. “And then it was too late.”

The Morris Island Lighthouse was automated on June 22, 1938. Historical records indicate that Hecker was transferred to another position within the lighthouse service. Then in 1956, with erosion imperiling Morris Island Lighthouse, the Coast Guard announced plans to build a new lighthouse on Sullivan’s Island and to deactivate Morris. The Morris Island Lighthouse was decommissioned in 1962 and replaced by the modern Sullivan’s Island Lighthouse — its official name is Charleston Light — which was commissioned on June 15, 1962. Its unique triangular design allows it to withstand hurricane-force winds up to 125 miles per hour. The new lighthouse also contained a modern luxury that helped keepers stay comfortable during the sweltering Lowcountry summers: air conditioning. Lighthouse keepers lived there until 1975, when it became fully automated.

Much to her delight, Violet’s daughter’s and grandchildren’s curiosity has been piqued by the family’s upbringing on Morris Island. “They were very excited to learn the history,” enthused Violet. “They were very proud they had a grandma who grew up at a lighthouse.”

For more in-depth reading, you can read historian and former Save the Light, Inc. Director Douglas Bostick’s book, “The Morris Island Lighthouse: Charleston’s Maritime Beacon.”

Someday I may bring my grandfathers navy spyglass and donate it for display my dad is the little boy in the school kids picture William Hecker JR ,my grandfather is William hecker and my grandmother Esther ,We would visit in Charleston South Carolina when we were kids ,my dad died few years back but gave me the spyglass before he passed ,how was a military man his whole life who had 6 kids I am the youngest Alan Hecker I live in Suffolk Va

So nice to know the history of my grandfather and grandmother Mr William Hecker and Esther Hecker whom I really didn’t know that much about them and only visit a few times our father William Alexander Hecker Jr. was in the military was gone alot and did not talk about his bringing up when he was a child, but what I did know and was able to see my grandparents they were very sweet.

Sandra Hecker-Lawrence

Portsmouth, VA.

would loved to here more about my grandparents

Would live to order the historical book. How can I get a hold of it.

Greetings Sandra, I did a Google search of the book’s title “The Morris Island Lighthouse: Charleston’s Maritime Beacon” and it looks like you can get it on Amazon.com, and Arcadia Publishing among others. Just choose your favorite place and price.