EMS Dads

In mid-September 2011, 32-year-old Pete Levine jumped into an emergency responder vehicle and rushed off with a siren wailing overhead on his first medical call for Charleston County EMS.

Levine had only been on the job for a short time, but was now speeding toward Dorchester Road where a multi-vehicle rollover had suddenly put multiple people in harm’s way. As Levine felt the adrenaline and precious seconds ticking by, he could only hope and pray that he and other responders would not arrive too late.

“I remember pulling up on the scene and being struck by the calmness of the experienced police officers, firefighters and my EMS co-workers despite the chaos around them,” recalled Levine.

Despite his early anxiety, Levine, now 46, came through the moment with the satisfaction of helping to turn a crisis back into a sense of normalcy.

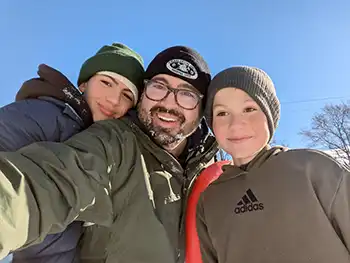

Since then, Levine has not only become a father of two boys, but is also one of many dads across the state who have gotten used to being taken for granted by people depending on him for all kinds of emergencies and needs.

“Being an EMS dad means juggling two demanding roles: serving the community and being present at home,” said Kelly Watson, marketing director of the South Carolina EMS Association in Winnsboro, South Carolina. “It is not uncommon for these providers to work a 24-hour shift, respond to intense emergencies, then head straight to a school play or coach their child’s sports team with little-to-no rest. The job is physically and emotionally exhausting, yet many EMS dads still make time for their families.”

Fire Dads

Mount Pleasant native Paul Sottile is one such dad. Having joined Sullivan’s Island Fire Department in 2017, the 37-year-old Sottile has a 2-year-old boy who sometimes gets to see where his dad works with the big red fire engines, the hoses, the sirens and the firemen’s uniforms.

But during his 24-hour shift, Sottile must remain on constant alert for not only the routine fire, but any nearby emergency in which he might have to save a life.

“One of my first calls was cardiac arrest of an island resident,” he said. “I just remember everything happening very quickly, and it was neat to see a lot of people/agencies working together.”

On any given call, Sottile might have to serve as a driver, pump operator, marine boat operator or aerial operator, and he is also in charge of pre-plans for island safety.

When asked if being a dad has altered his approach to first responder work, Sottile said only in the sense that he is now even sharper on both sides of the fire engine.

“I just enjoy serving the community and working with island residents and beach rescues,” said Sottile, who followed in the footsteps of his father, who served as a firefighter on the island in the 1990s. “The biggest challenge for me now is not only fighting fires but budgeting time with my wife and my son. Working a 24-hour-on, 48-hour-off schedule, I have to make sure when I am off that my family gets my full attention.”

Levine added that while it is sometimes hard for him to “work a holiday or leave my family to work during hurricanes,” he couldn’t imagine doing another kind of work.

“Like many young people, I didn’t know what I wanted to do as a career, but I knew I wanted to help people,” he said. “I thought about the fire service and nursing, but I was offered a free spot in a paramedic class while I was on the waitlist for nursing school.”

Watson shared that throughout South Carolina, there are approximately 13,968 active certified EMS providers such as Levine and Sottile. Urban counties like Richland, Horry, Greenville and Charleston see the highest number of emergency calls due to larger populations and the influx of seasonal tourism.

But before they can begin providing life-saving services, new responders are required to have a minimum of 200 hours of training, which includes instruction in:

- Pediatric and geriatric care

- Behavioral health

- Infectious disease control

- Disaster response

- Skills labs and clinical experience

“All trainees must also pass national written and hands-on exams,” Watson said. “Typical completion time is about three-to-six months.”

Added Watson, “Paramedics are required to complete 1,200 to 1,500 hours of training over about a year, which include advanced classroom instruction, hospital rotations and ambulance internships and completing certifications in trauma care, cardiac life support and emergency pediatric care.”

Watson continued, “EMS professionals are no longer just emergency responders. They are healthcare providers, problem solvers and community health advocates.”

And especially now that they are dads, Levine and Sottile wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Although it might not happen as often as we’d like, occasionally we get to save a life,” Levine said. “And there is no greater feeling in this world.”

By L. C. Leach III

Leave a Reply