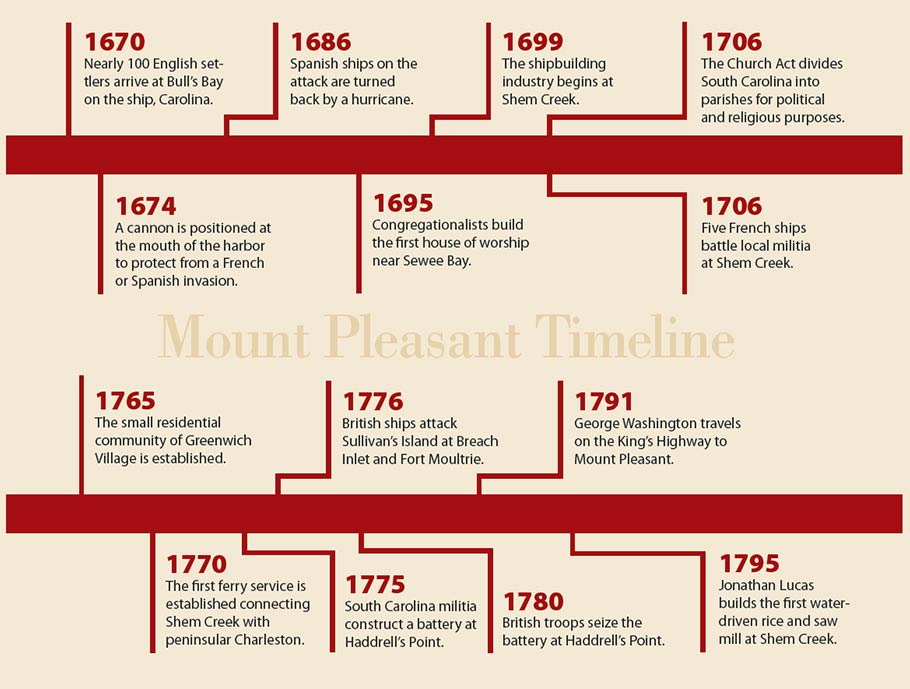

As Charleston celebrates its 350th birthday this year, let’s acknowledge a milestone for Mount Pleasant, too: 340 years and counting. In the next few editions, we’ll explore our town’s history, one century at a time. Let’s begin!

Before the arrival of English settlers to the Lowcountry in 1670, there were several Native American tribes east of the Cooper River. The Kiawah and Santee lived along the river, while the Wando tribe was near the mouth of the harbor and the Etiwan were on Daniel Island

The Sewee inhabited the northern reaches of present-day Mount Pleasant and beyond, which provided sustenance for their daily lives as they ground acorns and nuts to make bread, hunted deer and dined on shellfish, using the shells to skin and scrape animal hides. Their oval-shaped huts were fashioned from local wood and covered with Spanish moss and palmetto fronds.

In 1670, the Sewee spotted Carolina, the first English ship, sailing into Bull’s Bay. The ship had overshot its destination of Port Royal to the south, but the mistake was serendipitous. The Sewee and Kiawah welcomed them warmly and convinced them that they would be better off staying in this area. One English passenger wrote of being invited to Awendaw to the “Hutt Palace,” home of the Sewee leader, whereupon the English dignitary William Sayle was ceremoniously carried inside. Instead, the settlers put down roots west of the harbor on today’s site of Charles Towne Landing State Park.

A decade later, the newcomers moved their settlement to the peninsula. Florentia O’Sullivan, one of the original passengers on the Carolina, was granted 2,340 acres of land east of the Cooper River at North Point, also called Oldwanus Point (later becoming Old Woman’s Point), near the current Patriots Point. He was commissioned the surveyor general of the colony, and his duties included monitoring the harbor for any signs of a Spanish or French invasion.

Other Europeans came soon thereafter. Over 400 Huguenots arrived in the 1680s and settled on the east branch of the Cooper River, establishing a “French Quarter” there.

Fifty-one Congregationalists from New England arrived at Sewee Bay in 1695 and established several large plantations at Wappetaw, the area between the Wando River and Sewee Bay. They also built a meeting house, which may have been the first building to be constructed as a place of worship east of the Cooper. Congregationalists also settled on the Cainhoy peninsula.

The various groups of white colonists maintained an amicable relationship with the Sewee tribe, which paid off when the Native Americans reported five French ships at Sewee Bay in 1706. The local militia, under the leadership of Colonel William Rhett, met the French forces at Abcaw (now Shem Creek) and killed or captured half of the 160 invaders.

Twenty years earlier, Spanish warships from St. Augustine attempted an invasion but were halted by inclement weather in what came to be called the Spanish Repulse Hurricane. The storm may have saved the locals from that invasion, but 20 subsequent hurricanes wreaked havoc on the area over the next 100 years.

In the early 1700s, rice plantations in the Lowcountry multiplied, as did the number of African slaves, with thousands being imported to the region each year. Farms of other types were established, too. Abcaw was the site of a 400-acre vegetable farm called Hobcaw Plantation. Colonel Alexander Parris (think Parris Island) owned Hog Island (now Patriots Point) along with the once-lush Shute’s Folly (the site of Castle Pinckney), which became known for its 1,100-tree orange orchard. Mount Pleasant Plantation, just south of Shem Creek and originally called Hog Island Hill, was the home of well-known Charleston merchant Jacob Motte, who likely used it as his country retreat.

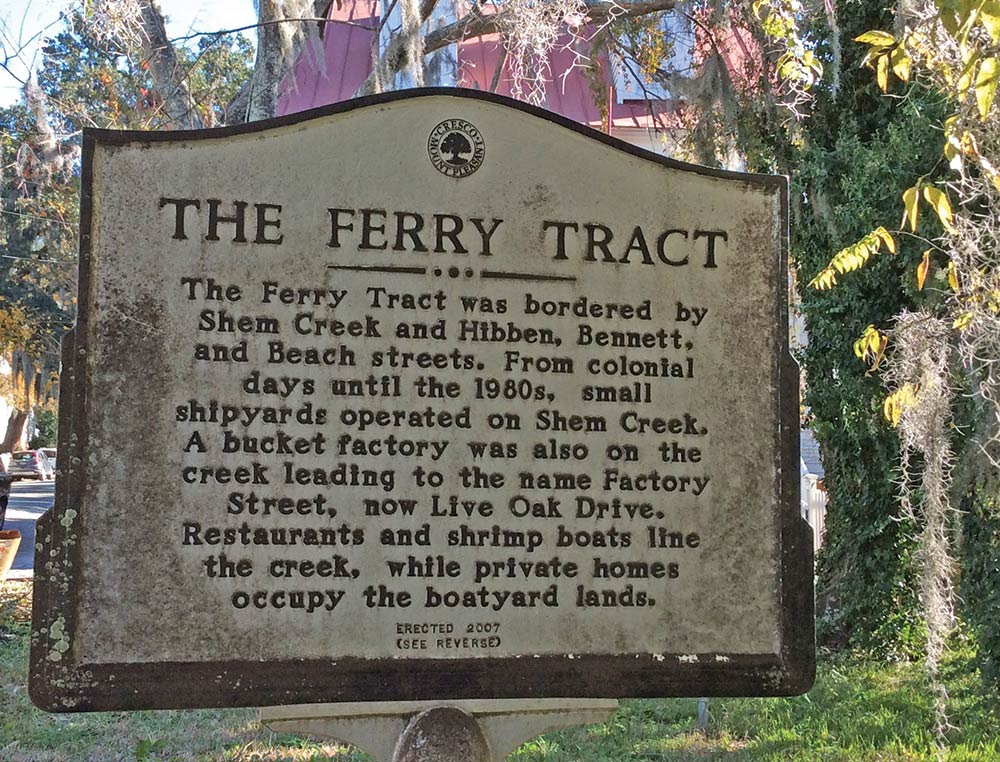

Shem Creek had many names through the years, usually related to the owners of nearby properties (Parris Creek, Dearsley Creek, Lempriere Creek, Rowser Creek, etc.). The area was a hub of activity with a brick-making establishment, a rice mill and sawmill, but the creek’s real identity was in the shipbuilding industry. The nearby Hobcaw Plantation was even referred to as Shipyard Plantation. Shortly before the war, one ship that was built there, Liberty, depicted on its bow a likeness of William Pitt, the outspoken member of Parliament who advocated for the colonists.

James Hibben purchased a portion of Motte’s Mount Pleasant Plantation in 1770 and began a ferry service connecting Shem Creek with peninsular Charleston, docking downtown at the foot of Queen Street. The fare on these barges was 33 cents per person; carriages were 75 cents or $1.75 (two- and four-wheeled respectively). Ferries to Georgetown also left from Shem Creek twice a week.

Ferry service to downtown Charleston was also available at Haddrell’s Point. It was the terminus for the Georgetown Highway, part of the King’s Highway from Virginia (which included present-day Coleman Boulevard). On his famous trip to the Lowcountry in 1791, President George Washington took a ferry from Haddrell’s Point into the city. A few decades later, John C. Calhoun accompanied President James Monroe downtown by ferry.

Haddrell’s Point served another important function during the Revolutionary War. A battery with 1,700 men and four 18-pound cannons was constructed in December 1775 by local militia. Six months later, it afforded back-up protection during the famous British attack on Sullivan’s Island where British forces were halted at Breach Inlet and Fort Moultrie.

During their subsequent occupation of Charles Town in 1780, 2,500 British soldiers took possession of Haddrell’s Point and used it as a prison for captured Patriots; a house at 111 Hibben Street became British headquarters. Some prisoners were kept at nearby homes but were allowed to wander six miles in any direction as long as they didn’t cross water.

Shortly before the war, 100 acres of land bordering Mount Pleasant Plantation were purchased by Jonathan Scott, an Englishman, who developed a small residential community he named Greenwich Village. This was the birth of the Old Village we know today.

By Mary Coy

Leave a Reply