There is perhaps nothing that defines a person more than their ability to accept who they are, where they came from and where they are going. And there’s no better time than right now to embrace acceptance — a year that has tested all our boundaries and shaken us to the core.

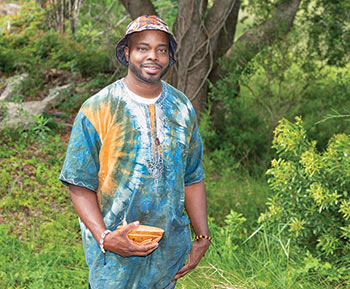

We spoke with Charlton Singleton, co-founder of the Charleston Jazz Orchestra and member of the Grammy-winning band Ranky Tanky, and Chef Benjamin “BJ” Dennis, recent winner of the Charleston Food & Wine Marc Collins award. Both born and raised in the Charleston area, these two ambassadors of Gullah culture are proud to incorporate aspects of local tradition into their craft. As Singleton and Dennis explained, Gullah — the culture of slaves and their descendants who lived in coastal South Carolina — is an innate part of their being.

As they strive to create a more global audience for Gullah through their respective arts, Dennis and Singleton have come to understand their own roots more clearly. As with most self-discovery, it was a process that culminated in deeper respect for the intersection of history, dialect, food, music and so much more.

At a time when we’ve been asked to question our values, Singleton and Dennis do not hesitate to hold onto what they know is theirs: a history shaped by blood, sweat and tears; a people fierce in their love of the land and each other; and an understanding that while we might all be different, we have more in common than we can imagine.

MOUNT PLEASANT MAGAZINE: Would you say you grew up Gullah?

CHARLTON SINGLETON: Absolutely. I was Gullah from the moment I was born. That’s how my family and my neighbors spoke — not that anyone mentioned the word Gullah. We didn’t see ourselves or our community as different from everyone else’s because it was all we knew.

BENJAMIN DENNIS: Exactly. It was part of my childhood. You never thought about it; it was just our culture.

BENJAMIN DENNIS: Exactly. It was part of my childhood. You never thought about it; it was just our culture.

MPM: When did you decide to infuse Gullah into your art form?

CS: Growing up and going to various African American churches, you experience music a certain way. Here, that way is Gullah. While he’s not a descendant, Clay Ross, our guitarist, has been a disciple of the music for a long time, and when he approached us to go out and play Gullah for the world, we initially didn’t know why. And so he explained that we could take the concepts and grow them by putting our own spin and interpretation on the music. And that made a whole lot of sense to us. Ranky Tanky means “work it,” and that is exactly what we do.

BD: I started working in local kitchens when I was 19 years old. I was always intrigued with history, especially African culture, but it wasn’t until I left Charleston that it really occurred to me how special it was. I was working in the British Virgin Islands with West Indian chefs who put their spin on specials, and that inspired me to do the same. I’d cooked local Charleston food my whole life, but it became about the importance of being unapologetic about your roots. And so when restaurant pop-ups started taking off in Charleston around 2010, I jumped onboard and started cooking my take on authentic Gullah food — fresh, the way I grew up eating it.

CS: It really took Clay being from the outside to look in and hear the music a different way, [versus] someone like me, who had grown up with it my whole life.

CS: It really took Clay being from the outside to look in and hear the music a different way, [versus] someone like me, who had grown up with it my whole life.

BD: Agreed. Sometimes when you grow up in the middle of something, you have to walk away to see it for what it really is.

MPM: Do you consider your interpretation of your culture authentic?

BD: To a certain extent, but it’s also an interpretation of foodways that have been lost — old-time recipes, word-of-mouth you can’t find in a cookbook or variations in those cookbooks. Talking with elders, looking at old documents and understanding that a lot of these cookbooks were written by Colonial housewives who got recipes from their cooks who might have left something out — because no one ever tells you the whole recipe. I am able to use those avenues as a jumping-off point and interpret from there.

CS: We came up with this idea to present our music decidedly as not authentic. In its purest form, Gullah is singing and clapping your hands and feet. So, even before we play, just having a drum set or a plugged-in guitar means we’re introducing a contemporary version. The last song on our album “Good Time” is the purest form of Gullah music we represent. It’s called Shoo Lie Loo, and it is singing, clapping and a tambourine. That’s it. We incorporated what a lot of people know, like jazz, into these Gullah songs to make them different and universal.

MPM: In a way, you are both historians. Do you look at it like that?

BD: As you retrace old dishes, you retrace history and connect people to that heritage. I would say that food tells a true story of history. It’s not just fried chicken and mac ‘n cheese — it’s deeper than that. It relinks our culture with that of West Africa, Central Africa, etc. Food is the common denominator. Just think about how rice made Charleston one of the most powerful cities in the Colonial period. I research the ingredients right alongside the dishes.

CS: We take what we are representing very seriously. It’s one thing to play here, where people understand what Gullah is, but the moment you set out of town, you are officially representing your community. It’s true that unless you are a scholar or have family from here, the audience we run into doesn’t know a lot about the Gullah culture — [maybe just] an idea about Gullah-related items, such as sweetgrass baskets, “Kumbaya” and hoppin’ john. When I’m on stage telling stories about these things, it begins to click. People realize they might have heard the song before, or at least a slightly different version of it. Gullah has actually informed a bunch of styles of music — jazz, folk music, gospel and spirituals — because it was started so long ago. So, when a woman in the Midwest came up to me and said she remembered singing a similar song when she was at camp as a little girl, I could point out that Gullah was the root, and the connection was made.

MPM: What is your intention as you introduce Gullah to the rest of the world?

BD: To continue the work of folks who have gotten the message out there before me — community activists, such as Queen Quet and Sarah Diaz. Using social media and my status as a chef, I can help channel that energy to let people know that this culture is still vibrant, and we are still pushing.

CS: Likewise — it’s a way to entertain people and teach them, too.

MPM: Did you know each other before this interview?

BD: Absolutely. I really appreciate the talents of Ranky Tanky. Kevin Hamilton, their bassist, is actually my cousin. Their songs take me right back to my grandmother’s church — old and small, with maybe 20 people there. But the energy was loud and vicarious with clapping and chanting.

CS: I am familiar with BJ’s food and have enjoyed it. Now, don’t ask me how to prepare it because I couldn’t tell you. There is something so special about the way my parents and grandparents prepared dishes like hoppin’ john or shrimp ‘n grits. It’s uniquely Gullah, and that’s the way BJ cooks it.

By Pamela Jouan

Leave a Reply