As Southerners, many of us were bred with a deep resentment toward Northerners due to their victory in the “War of Northern Aggression” and the resulting stories that passed down for generations about how Union soldiers hijacked crops, animals and silver from the Confederates, looting and burning their houses, consequently leaving many of our ancestors destitute. Equally frustrating to many South Carolinians was that after the war ended and emancipation had taken effect, there was no longer anyone to work the rice or cotton fields or to maintain plantation homes and properties. With no crops to grow and sell, the once thriving local economy plunged into such a state of disrepair that whites as well as Blacks found themselves starving.

As if times weren’t tough enough in the 1890s, three devastating hurricanes swept through Georgetown County, flooding the rice fields with salt water and damaging the riverbanks beyond repair. With little hope and scarce options, former planters listed their properties for sale.

In the meantime, the brackish rice fields of Georgetown County became a haven for so many species of ducks, legend says the skies were often darkened by the multitudes migrating along the Atlantic Flyway, a busy thoroughfare for waterfowl traveling from Greenland and passing by our shores on the way down to the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1894, when President Grover Cleveland learned of Georgetown’s overflowing duck population, he traveled to the Santee Gun Club with high expectations for a successful hunting excursion. According to Mary Boyd, volunteer at the Georgetown County Museum, he was not disappointed: in a single day, the president and his group shot 401 waterfowl. Of equal newsworthiness, while enjoying his time in the Lowcountry, the president, a large man of considerable girth, plopped out of a boat and into the pluff mud. Fortunately he was rescued, but the quagmire ate his boots. As the president was traveling with journalists, these stories quickly circulated throughout various news outlets, and word of Georgetown’s well-stocked waters broke the proverbial dam.

When our elite neighbors to the north heard about Georgetown County’s world-class duck hunting, wealthy investors descended upon the region and began buying up the very same plantations that their contemporaries’ fathers and grandfathers once exploited, transforming them into grand hunting lodges or winter vacation homes in which to entertain friends. This time, because these landowners hired struggling local whites and Blacks to rebuild and rehab the manors and clean up the land and bought their supplies from shop owners on Front Street, South Carolinians were grateful for this second invasion from the north. To this day, Georgetonians revere the investors of bygone decades who pumped money into the broken economy. As George Rogers notes in his book “The History of Georgetown County South Carolina,” “Without these northern plantation owners, Georgetown County might not have survived the Depression.”

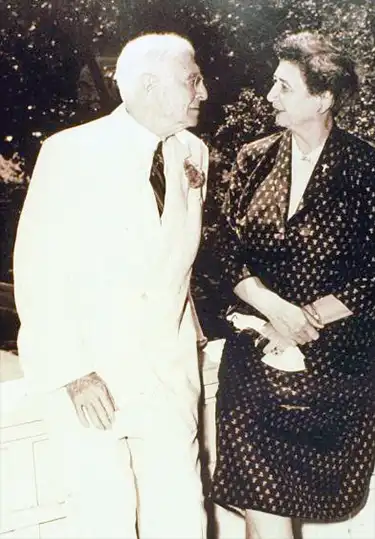

The Baruchs

One such venture capitalist was Bernard Baruch. Originally from Camden, South Carolina, Baruch moved to New York with his family when he was a child and went on to become the king of Wall Street and advisor to presidents. In 1905, Baruch purchased Hobcaw Barony, a 16,000-acre tract of land in Georgetown County. Mary Miller, author of “Baroness of Hobcaw,” related that the property was once home to 11 plantations and boasted “90 miles of roads, four bridges [sic], the church, two schools, the dispensary, docks and water towers, boat landings and stables.” According to Richard Camlin, director of education at Hobcaw Barony, there were at least five former slave villages at the time the Baruchs made their purchase. Several homes for white employees were also built on the property because, according to Miller, “The Baruchs employed over 100 people: cooks and domestics, farmers, mechanics, drivers, hunting guides, gardeners and general laborers”. Most resided on the self-sufficient estate.

Of note, the word “Barony” was not in reference to the title of a nobleman, rather it was the measure of 12,000 acres granted by King George I to one of eight Lords Proprietors to the Carolinas in 1718, according to Hobcaw Barony’s website.

Baruch’s daughter Belle, who spent much of her childhood at Hobcaw Barony, was enchanted by the magical world of forests and swamps, the plants and flowers that grew in them and the wild hogs, bobcats, alligators, snakes, foxes, deer, coyotes, birds, ducks and fish that resided in the brush and murky waters. As a result, over her lifetime, Belle developed a deep passion for the ecology of the land and had the foresight before she died to put the property into a conservation trust so that it can never be developed.

Belle went on to become a world class sailor and equestrienne who amassed an impressive collection of trophies. Also, she was a hunting enthusiast and, according to Camlin, a pilot of her own two planes for which she installed a runway and a hangar on the property.

The Luces

When in residence at Hobcaw Barony, Baruch and Belle invited a number of luminaries to stay at Hobcaw House and Bellefield, two respective mansions that they commissioned to be built on the grounds. Visitors included Winston Churchill, Irving Berlin, H.G. Wells, President Franklin Roosevelt, as well as Henry Luce, philanthropist and founder of Time, Life, Fortune and Sports Illustrated magazines. His wife, Clare Luce, a writer and editor who also went on to become the first female ambassador to Italy, was a former paramour of Baruch’s, who encouraged the couple to purchase property in the region.

In 1936, the Luces bought a plot northeast of Charleston called Mepkin, named for the peaceful and tranquil land once roamed by Native Americans before it was transformed by Henry Laurens, president of the First Provincial Congress in South Carolina, into a 7,200-acre rice plantation. Although the Luce’s never lived on the grounds, they commissioned the acclaimed landscape architect Loutrel Briggs to design the gardens. In 1948, Luce was offered $250,000 for the property and sold all but 3,000 acres, which he and Clare donated to Trappist monks of the Abbey of Gethsemani based in Kentucky.

Not long after, in November 1949, the monks arrived on the land where they established Mepkin Abbey as their home and place of worship. Since then, the monks have generously opened the grounds to the public every day, and there is a 45-minute guided tour at 11:30 a.m. every Tuesday through Thursday, and on Saturdays, which includes attendance of the midday prayer services and some background history on Mepkin.

For an updated tour schedule, visit mepkinabbey.org. While onsite, visit the gift shop, which sells honey, mustards, jams, mushrooms and plants, all handmade and grown by the monks. And stroll the gardens where you’ll find several cemeteries, one of which is the resting place of the Luces.

The Vanderbilts

Once home to eight plantations, the nearly 20,000-acre stretch of land along the Waccamaw River called Arcadia was acquired as a hunting preserve in 1906 by Dr. Isaac Emerson. A multi-millionaire from Baltimore, Emerson was an explorer, a sportsman who raced yachts and the grandfather of George Vanderbilt, with whom he enjoyed hunting and fishing and to whom he left the property in 1931. According to Ducks Unlimited, when Lucille “Lulu” Vanderbilt Pate inherited Arcadia from her father George W. Vanderbilt III in 1961, she and the family donated much of the property to conservation easements, because as her son Matt Balding said, “Some things are just more valuable than money.”

Tom Yawkey

Then in 1925, Tom Yawkey, owner of the Boston Red Sox, outdoor enthusiast and conservationist, bought 20,000 acres encompassing South, Cat and North Islands, which were donated in his will to what is now the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. According to the Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center, this conservation “established the Yawkey Foundation to ensure the continued management of the vast wildlife preserve.”

According to South Carolina’s Hammock Coast website, Cat, North and South Islands are in Georgetown County’s portion of the Intracoastal Waterway at the mouth of Winyah Bay.

The Huntingtons

A few years later, around 1930, Archer Huntington and his wife Anna arrived in Georgetown County after they discovered an advertisement in the New York Times marketing the sale of a hunting lodge called Brookgreen. Looking for a warm place to spend winters so that Anna could recover from tuberculosis, the Huntingtons traveled by boat up the Waccamaw River, the only way to approach the land at the time, and immediately fell in love with Brookgreen. The son of a railroad baron and a scholar in his own right, Huntington was one of the wealthiest men in America, according to Lauren Joseph, vice president of marketing at Brookgreen Gardens. Joseph added that Anna was a flourishing sculptor during the 1920s, a time when few women could aspire to become successful artists or high wage earners, making over $50,000 (roughly $700,000 in today’s dollars) per year from commissions.

Although such wealth certainly afforded the Gilded Age lifestyle, the Huntingtons preferred to spend their time surrounded by art, books, nature and animals. Having married in their 40s, they did not have children, and the philanthropically-minded couple quickly realized that the beauty of Brookgreen should be conserved so that it could be shared in perpetuity. On July 13, 1931, they incorporated Brookgreen as a private, nonprofit corporation, and it is still run as such today by a board of trustees, which Anna served on until 1972 before her death in 1974. As Joseph said, “The Huntingtons were early environmentalists, and their mission to preserve, conserve and educate the public about indigenous animals and plants continues to thrive at Brookgreen Gardens.”

With 9,000 acres spanning between the Waccamaw and the Atlantic, Brookgreen once housed four different plantations. As such, many formerly enslaved and their descendants were still living on the land by the time the Huntingtons acquired the property. Mr. Huntington hired the freemen to build a temporary home at Brookgreen that he and Anna could live in while constructing their Spanish-style castle called Atalaya on the beach that now bears their last name; transform the gardens; and build a schoolhouse on Sandy Island.

As Brookgreen, the first public sculpture garden, opened in 1931 during the throes of the Great Depression, locals were exceptionally grateful for opportunities for paid labor. Originally, the gardens were meant to feature only Anna’s sculptures, but during that time of scarcity for many artists and patrons alike, the Huntingtons also started buying and commissioning pieces that would enhance Brookgreen’s collection. Due to the number of women artists featured in the sculpture gardens, Brookgreen is recognized on the National Register of Historic Sites.

By the start of World War II, 100 plantations in Georgetown County were owned by illustrious New Yorkers who knew the whole world, and yet they chose this region as their playground. Over the decades since the war ended, development and climate change have culled the vast duck population in Georgetown County that originally attracted Northerners to the area, drawing a close to yet another chapter in our rich history. Without the restoration, preservation and conservation that our Northern neighbors contributed to this area, our thriving economy would not be what it is today. Additionally, with hundreds of thousands of acres in conservation easements, the Hammock Coast, east of the Waccamaw River, is protected forever from over-development, a huge gift to our coastal community.

So next time, instead of side-eyeing that damn Yankee sitting next to you at the bar, toast him with a glass of good old-fashioned moonshine or a locally-brewed cold one and give him a pat on the back. Because in case you haven’t noticed, not much has changed: we are in round three of Northern invasions and chances are that guy is looking to buy your house at top dollar, no matter what the current interest rates may be.

By Sarah Rose

Leave a Reply